At Quanta Magazine there was a long interview entitled "How Did Multicellular Life Evolve?" After some introductory discussion between Janna Levin and Steve Strogratz, Strogratz makes the claim that multicellular life evolved independently 50 different times. If that is true, then the explanatory shortfalls of Darwinism are vastly worse than most people think. Thinking of times long before mankind appeared, the average person thinks of maybe three main miracles of innovation that biologists have trouble explaining:

(1) The origin of prokaryotic cells.

(2) The origin of vastly more complex eukaryotic cells.

(3) The origin of multicellular life.

But if, as Strogratz suggests, multicellular life appeared independently 50 different times, then the number of required miracles of innovation is multiplied many times. The situation would be like this:

Miracle #1: The origin of prokaryotic cells.

Miracle #2: The origin of vastly more complex eukaryotic cells.

Miracles #3, #4,#5, #6, #7, #8, #9, #10, #11, #12, #13, #14,#15, #16, #17, #18, #19, #20, #21, #22, #23, #24,#25, #26, #27, #28, #29, #30, #31, #32, #33, #34,#35, #36, #37, #38, #39, #40, #41, #42, #43, #44,#45, #46, #47, #48, #49, #50, #51, #52: Fifty independent origins of different types of multicellular life.

But if so many independent origins of different types of multicellular life were required, why is it that this is so rarely mentioned? Probably because it's another of the endless cases of biologists sweeping under the rug their explanatory shortfalls. But Strogratz lamely suggests a different answer, saying this:

"Well, I think when we were in high school and they were teaching us biology, they didn’t know that. But it’s now understood that, you know, in all these different kingdoms or whatever they call them in biology — so whether it’s animals, plants, fungi — they all figured out their own way to do it, to go multicellular."

Strogratz should be scolded here for using language suggesting that one-celled life can "figure out" a way to become multicellular life, which is rather like suggesting that bricks figure out a way to become ten-story apartment buildings with plumbing and electricity.

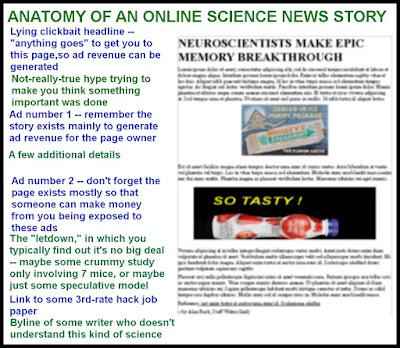

We get some introductory comments about biologist Will Ratcliff, who we are told "wants to induce a multicellularity transition in a single-celled organism," a yeast. It's some "getting a little cell clumping and calling it multicellularity" nonsense, like that shown in the visual below.

Nonsense like that shown in the visual above leverages ambiguity in the word "multicellularity." When you are talking about the main problem of explaining multicellular life, multicellular life should be defined as visible self-mobile organisms consisting of complex anatomy requiring many different types of cells and higher levels of organization such as appendages and organs. Or better yet, use the term "anatomically complex organisms" rather than "multicellular life," which makes it clear that you are talking about something vastly more than just clumps of cells.

I am stunned to find that we get a little critical thinking from one of the interviewers (given the history of the staff at Quanta Magazine acting like scientist bootlickers). Strogratz says this:"But as we’ll hear from Will, it is controversial. There are colleagues of his who feel what he’s doing is irrelevant to the history of life on Earth, that he’s just doing something in the lab, and it may be telling us very little about what happened in real biology."

We then get biologist Ratcliff beginning to talk, and he starts speaking in self-contradictory ways. First, he calls cells "fantastic biological machines," speaking as if he understood their very high complexity and organization. But he then very quickly reverts to engaging in the shadow-speaking language that biologists love to use, in which vastly organized and enormously fine-tuned things are described as if they were mere shadows of what they are -- this being done to help make tall tales of their accidental origins sound less far-fetched. Ratcliff says, "And once sort-of cells evolved, they really took off, and it has been the sort-of basic building block of life for the last three-and-a-half billion years." There is nothing "sort-of-basic" about a cell, and it is profoundly misleading to call a cell a "building block," as building blocks such as bricks are very simple things without any complexity or information, and cells are enormously organized information-rich units with very high functional complexity. There is no reason why such misleading "building block" language needs to be used. You can express a similar idea without misleading people by saying things such as "cells are building components of organisms."

Ratcliff later continues his misleading use of shadow-speaking in which extremely organized and information-rich things are misleadingly described as mere shadows of what they are. He says, "All these basic building blocks of life, like DNA, which contains the, sort-of, code of the organism." DNA is an extremely complex molecule, and human DNA has billions of base pairs of information. So it is extremely misleading to refer to DNA as a "basic building block," a phrase suitable for describing simple things without complexity (such as a brick), but utterly misleading when used to describe DNA or cells. It is also not true that DNA "contains the, sort-of, code of the organism." DNA has no specification of how to make an organism or any of its organs or any of its cells or any of the organelles of such cells. The myth that DNA is a blueprint or recipe or program for making an organism is a deception that biologists have long been guilty of telling, even though many scientists have stated that such claims are false. Beware of any scientist using the words "sort of" or "basically" or "essentially," terms that they often use when they are making claims that are untrue.

Ratcliff reiterates the previous claim about 50 different origins of multicellularity, saying, "There’s at least 50 independent transitions to multicellularity that we know of." Ratcliff then engages in the same "figure out" nonsense talk that Strogratz had previously used. Ratcliff says that "animals...just start to figure out all of these innovations which are hallmarks of extant animals." This is not what evolutionary biologists claim about the origin of biological innovations. Instead they claim that there occurred accidental variations that luckily led to all kinds of wonderful biological innovations such as lungs and hearts and legs and wings. But a person hearing such claims of accidental inventions may recognize that such claims are nonsensical, intuitively sensing correctly that accidents do not produce complex inventions. So biologists such as Strogratz may have luck in fooling people if they claim that "animals...just start to figure out all of these innovations which are hallmarks of extant animals." But evolutionary biologists don't believe that any biological innovations of animals arose from animals literally "figuring out" anything.

We then have from Ratcliff this confession about the Cambrian Explosion about 540 million years ago, in which all or almost all of the animal phyla appeared rather suddenly in the fossil record:

"Before the Cambrian explosion, things were soft and gelatinous and didn’t have eyes or skeletons. It’s questionable if they had brains. They don’t have any of these things. And then in a relatively short period of time, just a few tens of millions of years, all of these things show up. And we think it’s probably due to these, like, ecological arms races, where you have predators attacking prey. The prey start evolving defensive mechanisms. So, you know, you have just this explosion of animal complexity in what appears to be a very short period of time in geological terms."

What we have here from Ratcliff is a very bad attempt at an explanation. He's basically saying all these marvels of biological innovation appeared, because creatures needed stuff. "They needed it" is not a credible explanation of why miracles of incredibly-hard-to-achieve organization would occur. Similarly, if you are at a junk yard, and you watch as 1000 scattered auto parts magically assemble into a car, you don't explain that miracle of organization by saying, "Well, I needed a car." The "arms race" metaphor is just another of the endless bad metaphors and bad analogies used by evolutionary biologists. An arms race is something that occurs between nations led by humans, not something that occurs in animals or imagined predecessors of animals.

Ratcliff then makes a very bad misstatement by claiming that multicellular life is 3 billion years old. There is no convincing record of any anatomically complex organisms existing before 1 billion years ago. Ratcliff may be referring here to a few cells clumping together in an unimpressive way, but that isn't real multicellular life, something like animals with complex anatomy. As a recent biology textbook told us on its page 9, "Complex multicellular animals appear rather suddenly in the fossil record approximately 600 million years ago."

Ratcliff then gives us this vacuous hand-waving attempt at explaining how multicellular life appeared:

"And you know, I think we should not think of it as one process, but something where there are ecological niches available for multicellular forms, and there has to be a benefit to forming groups and evolving large size. That benefit has to be fairly prolonged. And most of the time, there isn’t, but occasionally there will be an opportunity for a lineage to begin exploring that ecology and not be inhibited by something else that’s already in that space."

This is more vacuous "they got because it was useful" nonsense, that does not explain how miracles of innovation could have occurred.

A bit later we get more hand-waving vacuity from Ratcliff, more talk along the lines of "they got it because it was useful":

"But, once you start forming multicellular groups, you can participate in a whole new ecology of larger size. You might be immune to the predators that were eating you previously, or maybe you’re able to overgrow competitors for a resource like light. If you imagine that you’re, you know, an algae growing on a rock in a stream, single-celled algae will get the light but, hey, if something can form groups, now they’re intercepting that resource before it gets to you. They win, right? Or, you know, groups also have advantages when it comes to motility and even division of labor and trading resources between cells. So, there’s many different reasons to become multicellular. And there isn’t just one reason why a lineage would evolve multicellularity. But what you need for this transition to occur is those reasons have to be there, and that benefit has to persist long enough that the lineage sort of stabilizes in a multicellular state and doesn’t just go back to being single-celled or die out."

When evolutionary biologists lack any credible "how" in explaining biological origins (which is pretty much all the time), they start giving us "why" explanations like this, hoping that we don't notice that they are not addressing a "how" but only addressing a "why." And it is very strange that these believers that life arose through blind, unguided processes keep talking as if they believed in "why" driving everything.

Ratcliff then lets his guard down by confessing that evolutionary biologists do not really understand how multicellular life arose. He makes this confession:

"Big picture, we want to understand how initially dumb clumps of cells, cells that are one or two mutations away from being single-celled, don’t really know that they’re organisms — they don’t have any adaptations to being multicellular, they’re just a dumb clump — how those dumb clumps of cells can evolve into increasingly complex multicellular organisms, with new morphologies, with cell-level integration, division of labor, and differentiation amongst the cells. Just like, we want to watch that process of how do these simple groups become complex. And this is, like, one of the biggest knowledge gaps in evolutionary biology. I mean, in my opinion....We don’t really know the process through which simple groups evolve into increasingly complex organisms"

Ratcliff's commendable humility here lasts for about one minute. It is then immediately demolished and replaced by some ridiculous groundless boasting. He says this: "So, what we’re doing in the lab is, we are evolving new multicellular life using in-laboratory directed evolution over multi-10,000 generation timescales, to watch how our initially simple groups of cells — dumb clumps of cells — figure out some of these fundamental challenges." It's an unfounded boast. He is referring to mere cell clumping in yeast. There is no type of new organism produced by such experiments. Each of the little least clumps is just a crowd of one-celled organisms, not a new organism. You are no more producing "new multicellular life" by such laboratory work than you would be producing "new human life" by shouting "Free 100-dollar bills!" in Times Square to attract a flash mob. Crowds of one-celled organisms are not multicellular life.

I can understand why the Quanta Magazine interview has no photos showing the result of the Multicellularity Long-Term Evolution Experiment that Ratcliff is talking about. Showing a photo would show how trivial Ratcliff's results are. But doing a Google image search for that phrase, I find a university press release that shows the result of the experiment. It is the nothing-to-brag-about result shown below, about as impressive as getting a little algae slime buildup in your backyard swimming pool.

Laughably, Strogratz refers to this silly little result by saying, "That is incredibly ambitious. I mean, I hope the listeners get a feeling of the courage it takes." Equally laughable are some of the paragraphs we soon get, in which Ratcliff speaks all rapturously about these little disorganized clumps of yeast he got, as if he was trying to use every term he can think of to make them sound grand and glorious. Misleadingly, Ratcliff talks about the yeast producing "babies" when he merely means other cells. Misleading us, Ratcliff says this of his tiny yeast clumps: "They’re solving all these fundamental multicellular problems." But he gives away how little he has got when he says this: "You know, they’re bigger than fruit flies now. They’re large." Fruit flies are about three millimeters in size, which is about half the width of the nail on your pinky finger. Ratcliff's test tube clumps are not large.

Later in the interview Ratcliff complains about getting criticisms from either scientists. He suggests that other scientists were accusing him of inflating the importance of his work, and he sounds offended or indignant about having to defend the relevance of his work in growing test-tube yeast clumps. He gives us this confession: "Anytime you critique a paper in my field, you might think you’re critiquing the senior scientists on the paper, but they usually have a graduate student or a postdoc who wrote the thing." So senior biologists are very often putting their names on papers that were really written by graduate students without a PhD? That's another reason for distrusting papers in evolutionary biology and neuroscience. Ratcliff seems to make a kind of "let's not hurt the feeling of the tender graduate students" plea. Wouldn't it be better to help make them better scientists by giving them an idea of what kind of experimental research studies attract criticism because of their flaws?

Nowhere in the long interview with this multicellularity origin specialist do we get any reason for thinking that scientists understand how large mobile organisms with organs and limbs could have ever evolved from mere one-celled organisms. To the contrary, the interview suggests that scientists have no such understanding at all. The failure of scientists to give a credible account of the origin of anatomically complex organisms is only one of very many reasons why their "evolution explains us" and "Darwin explained how we got life so complex" claims are unfounded and untrue.

To show the untruth of big boastful claims that someone makes, make a collection of all the confessions that person makes that he would not make if his big boasts were true. For example, by noting how someone confessed that he owes very much money on his credit card, you can document that he's making unfounded boasts if he claims that he's doing great financially. To help show the untruth of claims that scientists make that they understand the origin of humans and other large enormously organized organisms, you can document as many cases you can find of scientists confessing that they don't understand how there ever arose things such as the first cells, eukaryotic cells, protein molecules, protein complexes, anatomically complex organisms, human minds, human memory, the origin of language, and the origin of a full human body during the nine months of pregnancy. To help show the untruth of claims that scientists make that they understand the origin of humans and other large enormously organized organisms, you can document as many cases as you can find of scientists confessing that they don't even understand things such as how proteins fold into the 3D shapes needed for their functions, how cells (lacking any DNA specification for how to make a cell) are able to reproduce, and how sexual reproduction ever arose. You can find an extremely long set of such confessions in my "Candid Confessions of the Scientists" post here.

Postscript: On the science news sites today (April 1), we have coverage of an Emory University press release entitled "A New Clue to How Multicellular Life May Have Evolved." It's about a scientist observing a type of one-celled life clumping into tiny disorganized swarms. We have no clear explanation of what this "new clue" is, and we get more suspicions that scientists without any real clue as to how multicellular life arose are grasping at straws.